One Championship: Bringing The Fight to Media

There's a billion-dollar opportunity for sports in Asia, and Chatri Sityodtong is unlocking it with MMA.

“If you look at the history of sports in Asia, we’ve always only imported. It’s time for Asia to have its own sports league.”

When I showed my friends this quote, nobody was sure what sport it referred to. Was it soccer, the most popular game in the world? Or table tennis, which China has dominated since it became an Olympic sport in 1988? Maybe badminton? There wasn’t a consensus.

To Chatri Sityodtong, however, the answer couldn’t be clearer.

Asia has been the home of martial arts for the last 5,000 years, with forms such as Wushu, Taekwondo, Karate, Muay Thai, and Silat. It has formed part of the history, culture, and tradition of almost every Asian country. And when you look at how Asian stars have broken into Hollywood and popular culture, martial artists have (always) led the way: from Bruce Lee putting kung fu in the spotlight in Enter the Dragon, to more contemporary movie stars such as Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, and Michelle Yeoh starring in the latest action films.

Sityodtong knows this at a deep level. He lives and breathes martial arts.

As a child, he spent his time training in Muay Thai. He went on to have a short but intense professional career, notching 30 fights under his belt. When Sityodtong swapped his career in the ring for one in finance, he never stopped training, even opening his own chain of MMA gyms. The biggest move would come in 2011 when he left finance completely to start ONE Championship, a sports promotion company.

This hasn’t been easy. Where sports like football and basketball may enjoy universal popularity, combat sports like MMA have a small audience. It’s harder to find skilled athletes, and needless to say, the violence doesn’t make it family-friendly. That makes the business of combat sports a lot more complicated since there are fewer sources of revenue.

But Sityodtong has made it work. Since its founding in 2011, ONE Championship has organised over 100 cards (events with headline matches and other less anticipated matches). More significantly, it has grown to become the second most watched sports league on social media, coming behind only the NBA.

There’s a lot of firepower behind ONE as well. It started off with a little seed money from Sityodtong and his friends at Harvard Business School but has since gone on to raise a whopping US$515 million. Investors include Sequoia Capital, Singapore sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings, Greenoaks Capital, and the Qatar Investment Authority. You couldn’t ask for a better cast.

But betting on what is essentially a media business isn’t something that investors typically do, especially when it isn’t already producing cash. What do they see in ONE? That’s what we’ll be looking at today. In this piece, we’ll cover:

The Warrior Founder: lots of founder CEOs have strong personalities, but few are like Chatri Sityodtong. The CEO of ONE Championship seems almost larger than life and his story lends itself to a degree of founder-product-market fit that you don’t see very often.

The Business of MMA: sports teams are fundamentally in the media and entertainment business, but they can have very different challenges. Unlike basketball or football, MMA remains a very niche sport, which means that monetisation is trickier since there aren’t billion-dollar TV deals lying around.

Distribution: ONE owes its explosive growth to social media and live streaming, which is something that wasn’t available to many sporting leagues in their early years. Social media impressions and views are usually seen as vanity metrics, but if you’re in the media business, that counts for a lot.

The Opportunity: There’s a lot of money in entertainment, but ONE will need to last long enough in the ring before it can reach profitability. A focused push might be what the company needs to gain market share.

The Warrior Founder

Chatri Sityodtong wasn’t always the man we know.

Born Chatri Trisirpisal, Sityodtong grew up in Pattaya, Thailand. He trained extensively in Muay Thai, and it was at the famous Sityodtong gym that his master gave him the ring name Yodchatri Sityodtong, or “Extraordinary Warrior”. Chatri loved Muay Thai. But he realised early on he wasn’t good enough to compete at the highest levels.

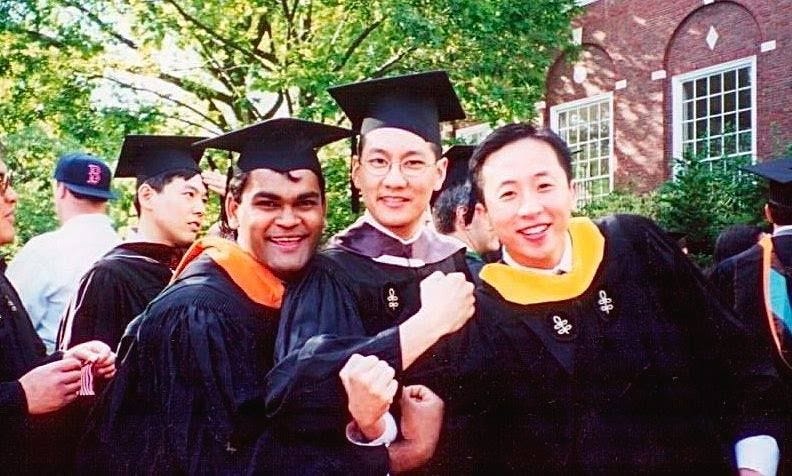

Finance, however, was on the cards. After finishing his undergraduate studies at Tufts, Sityodtong began his career as an analyst at Fidelity Investments. This didn’t last long. When Harvard Business School (HBS) offered him a place in their MBA programme, Sitoydtong took that chance, although not without hesitation. This was during the Asian Financial Crisis, and his family had just lost everything. HBS would open up many doors but it would also be terribly expensive.

At HBS, Sityodtong lived on ramen and $1.50 microwave meals. Between keeping up with his studies, networking, and tutoring students for daily expenses, Sityodtong managed to start a software company called Nextdoor Networks with his classmate Soon Loo in his second year. The two worked long hours to make things work, and this period would inform Sityodtong on the sort of people to hire. “I look for people who have the PHD factor – poor, hungry, and determined”, he would later say.

Over the next two years, Sityodtong and Loo would graduate from HBS and raise over US$37 million in VC funding for Nextdoor Networks. Investors included Sprint as well as Trinity Ventures, which had invested in Starbucks. Things were looking up and Nextdoor Networks even received a US$200 million acquisition which the duo turned down. Unfortunately, this was at the height of the dot-com bubble and the markets crashed shortly after. With cash running low and no further funding coming in, the duo were forced to sell the company in 2001 at a much lower valuation.

Sityodtong’s HBS credentials came in handy as he looked for his new gig. He first landed a job at JLF Asset Management, a New York hedge fund. Then, he moved on to Maverick Capital, a long/short equity hedge fund founded by Tiger Cub Lee Ainslie. After building a reputation in the business, he launched his own US$500 million hedge fund, Izara Capital Management. It was a hell of a ride, but 10 years in the business taught Sityodtong that this wasn’t what he was looking for. By his own account, he was a multi-millionaire and was set for life at age 37.

The financial crisis of 2008 was the trigger that made Sityodtong do a 180-degree turn.

In 2009, he moved to Singapore and started Evolve, an MMA gym that has since developed a name in the local arena. This let him practise the sport he loved while also providing for many Muay Thai martial artists he had known personally. His first trainer, Papa Daorung, for example, had been responsible for moulding several Muay Thai world champions but was still steeped in hardship and poverty. Working as an instructor at a commercial gym in Singapore increased his standard of living considerably.

A core problem was that MMA wasn’t popular enough for anyone to have a viable career. Scratch that – no sport was popular enough in Asia. This was perplexing for Sityodtong.

“Every region of the world has several multibillion-dollar sports properties. The US has the NBA, NFL and Nascar, and Europe has F1, BPL, Bundesliga and Spanish La Liga. All these properties are worth a few billion, up to US$40 billion to US$50 billion a piece. Asia has nothing on a Pan-Asian scale. So, there is no reason why this cannot rival the EPL, NBA or NFL, there’s no reason.”

It was a strong thesis, one that ESPN Asia senior executive Victor Cui believed in as well. Cui had been tasked to look for the next multi-billion-dollar opportunity and had turned over just about every rock in his search, from football, darts, to cheerleading. He finally arrived at his answer – MMA – when he met Sityodtong, whom Cui knew then as a former hedge fund manager turned gym owner. This would develop into something more.

The Business of MMA

In sports, there are but a few ways to make money. You can sell seats to fans, get sponsors to advertise at your event, and licence broadcasting rights to media publishers, with each more profitable than the last. Each segment, however, is important to ensure that revenue sources are diversified - ticket sales, for example, plummeted to near-zero during the initial Covid outbreak.

It’s a simple business model and one that has delivered a track record of healthy cash flows along with rising team values. Private equity firms have noticed and invested accordingly – the Golden State Warriors and Manchester City are some of the biggest names which are co-owned by investment funds. There’s a lot of money pouring into sports, especially into teams which have emerged from Covid relatively unscathed.

But those in the business of MMA haven’t had it this easy. In a sport where a fight is won by knockout or submission, athletes get injured often and severely. Where you might see a sprained ankle or a torn meniscus in most sports, it’s not uncommon in MMA to see a fractured skull or broken arm in one night. This creates several unique challenges.

First, running regular events is operationally difficult. Because of the high rate of injuries, athletes fight less, which makes it impossible to have a regular season. Where NBA teams might play 82 games and EPL teams 38 games in a season, the average MMA athlete fights only 2-3 times in a year, with fight promoters such as the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) hosting around 40 live events.

This means matchmaking fighters and putting together an exciting fight card can be a nightmare in itself. Plus, fighter promoters have to pay upfront costs and sell their own pay-per-view (PPV) packages and ringsides, something which other sporting leagues rely on their media partners for. The irregularity of this all means that companies like the UFC and One Championship are structured as fight promotion companies instead of sports leagues - they cannot afford to look too far beyond one night at a time.

Second, sponsorships are difficult to come by. Not all fights are created equal, and sponsors know that as well. But the very nature of the sport means that it’s impossible for a fight promotion company to guarantee or forecast what the returns on a potential sponsorship might look like. A fighter might be injured and unable to compete, or a lucky KO ends the entire match in two minutes. There isn’t much in the way of media assets that fight promoters can leverage, which means that fight promoters really have to squeeze as much as they can out of any limited real estate . As Jonathan Snowden writes:

“When you're a fighter, everything is for sale. Whether it's a patch on your crotch or the shirt on your back, every piece of visible real estate has value for a fighter who is about to appear on television. The agent's job is to fill that space, maximizing income and building relationships for the future. [...]

Fight shorts aren't a commercial product that companies are able to sell to the general public. What they are is a billboard for advertising that could appear in front of a television audience for up to 25 minutes. Short space is sold in four pieces: the crotch, the butt, and both thighs. The top agents have been able to score more than $30,000 per patch, but that's rare. For a television fighter who isn't a major star, the crotch and butt space are worth from $500-$2,000. Each thigh ranges from $250-1,500. Savvy agents can sell these spaces at a premium if they pitch it right.”

Whereas other sporting leagues might be able to stick a Nike or Emirates logo on an athlete’s jersey or sell 30 seconds of airtime during their half-time show for 5 million dollars, those in MMA are stuck fighting for scraps. The fight promotion companies can’t count on sponsorships as a source of reliable income, and the fortunes of the athletes depend heavily on the skill of the agents who represent them. It’s a tough racket.

Third, most people don’t have a natural affinity for MMA. Unlike sports such as boxing, wrestling or Taekwondo, there aren’t kids who grow up competing in MMA. This creates several problems, most importantly that there isn’t a pipeline of student athletes who turn pro, and consequently a lack of established organisations to facilitate development and accreditation. And when you consider that MMA is a full contact activity that viewers need a strong stomach to sit through, it becomes an incredible challenge to grow the sport.

Back to One Championship. Sityodtong and Cui had built a small but growing fight promotion company that hosted its first event in Singapore. From there, they slowly expanded to fight nights in neighbouring Southeast Asian countries, holding 11 events in 2014 to 14 in 2017. It was a slow and unprofitable grind.

“No broadcaster wanted to show our content, fans did not want to watch our show, athletes did not want to be part of the company and brands were not keen to invest. Governments also did not want us in their countries,” Sityodtong recalled.

Their growth trajectory would soon change. An investment banker that Sityodtong was working with for their Series C round - their Series A and B rounds were not publicly reported - shared an escalator ride with Sequoia India’s Shailendra Singh and made a literal escalator pitch. Singh bit, and within eight weeks, the US$100m round was closed with Sequoia and Mission Holdings as co-lead investors.

Content is King, Distribution is Queen

Sequoia's core thesis was that One Championship wouldn’t have difficulty generating revenue through licensing once it had reached a critical mass of viewers.

This makes sense. As we’ve covered earlier, broadcasting rights are the crown jewel of many major sports. They make up the lion’s share of total revenue, and the numbers are eye-popping:

The NFL generates US$12 billion a year from TV revenue, making it the most lucrative sport in the US (more on this from this fantastic Acquired episode Acquired)

The NBA makes US$2.6 billion a year from TV revenue, but that will likely triple in 2025 after their current media deal expires

Total broadcasting revenue for European football clubs topped €4.5 billion in 2021, making up 44% of total revenue

It’s crazy, especially when you consider that media has traditionally been thought of as a business with bad economics. And these figures are only set to rise as tech giants such as Netflix, Apple, and Tencent join in the bidding for these rights as they continue to expand the media properties they own. Sityodtong puts it this way: “If you have the three pillars of content, community, and transactions, then you are truly a part of somebody’s life, you have a very deep relationship with that customer.”

This explains why Sequoia wanted One Championship to build a great mobile app - and then give access away for free. Charging users a PPV streaming fee or subscription fee might allow a fighting promotion to generate revenue and be profitable early on in its business, but this would come at the cost of growth. Case in point: the UFC raked in over US$1 billion in 2022, but took 29 years to get there, with its first 8 years unprofitable. If One Championship could shorten that process by spending more upfront, they should definitely do it.

While this might sound like VCs letting their start-ups burn money for growth – ride hailing comes to mind - growth through a streaming app was particularly suitable for One Championship. For starters, there were still tailwinds in mobile adoption that the company could benefit from in 2017, especially as the market had not been overly saturated with apps. Moreover, MMA fights were perfect for mobile viewing. “72 percent of our matches end within a few minutes,” Sityodtong explains. “This is perfect for short-form content on a mobile device. You’re not going to watch a 90-minute soccer game on [a phone].”

Then, there’s the psychological aspect of things that comes with social media sharing. There is just something primal about violence that draws people in, and a mobile app facilitates its spread on social media. As Dana White, president of the UFC, wrote in an email:

"Everyone loves a fight. It's in our DNA. The example I like to use is that if you're in an intersection and there's a basketball game on one corner, a soccer game on another, a baseball game on the third, and a fight on the fourth, everyone will go watch the fight. And that's not only true, but it's something that cuts across all demographic and geographic barriers."

The numbers back that up.

Nielsen’s statistics showed that One Championship grew its total social media impressions from 352 million in 2014 to 8.3 billion in 2017, with total video views growing from 312,000 to 1.5 billion. more recently in 2021, total video views of ONE topped 13.8 billion, making One Championship the second most digitally viewed sports media property in 2021, just behind the NBA. For context, that’s double the 6.6 billion video views which the UFC garnered in the same period.

Covid-19 and the popularity of Tik Tok have obviously helped to boost these numbers, but it’s hard to deny that One Championship has been particularly effective at driving social media engagement. The quick bursts of action in MMA fit hand in glove with the shorter video formats that social media has been pivoting towards (Facebook/YouTube shorts, Instagram reels, TikTok, etc.), which means that it’s a safe bet that One Championship’s social media numbers are only going to grow.

This penchant for marketing might come from the founder-CEO himself. Since ONE’s founding, Sityodtong has not been afraid to step into the limelight and field media requests. In 2020, Sityodtong hosted The Apprentice: ONE Championship Edition, in which 16 contestants competed to join One Championship as a member of the CEO’s office. It’s exactly the kind of thing that helps with international branding, but also the type of thing that would lead to not always favourable comparisons with other larger-than-life personalities such as Elon Musk and Tan Min-Liang.

But in the media business, being able to get media attention is a good thing. As they say, there’s no such thing as bad publicity, and this has certainly been the case for One Championship.

Sequoia followed-up on its investment in 2018, leading One Championship’s US$166 million Series D round, with Temasek Holdings and Greenoak Capital joining in. And in December 2021, One Championship raised another US$150 million from the Qatar Investment Authority and Guggenheim Investments, bringing its valuation above the billion dollar mark.

So far, it looks like these VC dollars will return. One Championship has been executing Sityodtong’s licensing strategy, and they’ve inked deals with partners, including:

Amazon Prime in the US and Canada (>200 million subscribers)

FanDuel, an online gaming company, on its newly launched TV network

Star Sports, a division of Disney, to broadcast content in India

Beijing TV in China

Globo, to broadcast ONE fights to over 200 million viewers in Brazil

Clarosports, a multimedia sports information platform, to deliver live ONE events across Latin America (excluding Brazil)

beIN Sports, a Qatari state-owned media group, to broadcast ONE events in 24 countries in the MENA region

Seven Network, to broadcast live ONE events in Australia

These deals aren’t necessarily lucrative, but it shows that there is appetite for One Championship content. More importantly, the company’s expansion into the US has been through a deal with big tech (Amazon) instead of traditional TV networks, which underscores how much optionality sports properties such as ONE have gained as a result of competition in the streaming business. It’s not hard to imagine something like this being replicated for the UK, Europe, and China.

Knockout Opportunity

With all that talk about distribution, it’s easy to forget that One Championship, like every other business, needs a product. At the core of that product are its athletes.

Since its founding, One Championship has differentiated itself from other promotions by emphasising what Sityodtong calls “a culture of respect”. In comparison to the trash talking and blatant display of wealth epitomised by the likes of McGregor and Mayweather, ONE athletes have not been as loud, whether in the boxing ring or media room. This might have been a strategic decision instead of one driven by a purely moral imperative - the lack of humility would have been frowned upon by its predominantly Asian audience.

The athletes who have signed with ONE have also vastly improved when compared to its hatchling days. Rodtang “The Iron Man” Jitmungnon has become one of its most popular athletes with his ability to withstand damage in the ring, and ONE’s brilliant social media team has capitalised on this, whether with their explosive knockout videos or meme marketing.

Just take a look at the video below:

Athletes from other fighting promotions have also joined ONE, with the most notable being flyweight champion Demetrious “Mighty Mouse” Johnson from the UFC. It’s a sign that ONE has entered the wider MMA consciousness and that it isn’t just a niche Asian product.

Beyond what goes out on fight night, One Championship has also diversified and launched new offerings to expand its reach:

ONE Studios: a TV and film division that produces programs and films starring ONE athletes

ONE Esports: a gaming division that produces content with titles such as Dota 2, League of Legends, Counterstrike, and Overwatch

ONE Fantasy: a mobile fantasy fighting game that features ONE athletes

Some of these are great. Studios, for example, represents a continued investment in content revolving around its core product. Storytelling is at the heart of every enduring franchise, and crafting an arc for its athletes makes it easier for viewers to be emotionally invested in each fight. Documentaries such as All or Nothing, The Last Dance, and Drive to Survive have all helped to ignite interest in their sports, and this is a model that One Championship can easily follow.

Others are less so. Its mobile game has graphics that are reminiscent of the Street Fighter series and are a long way from comparable martial arts-based games such as the WWE and UFC series. And while Esports is the next huge consumer market, it’s hard to see how it synergises well with One Championship’s core offering. If digital sporting entertainment is the ultimate category that it’s going for, it’s going to take years before this effort bears any fruit.

Time isn’t something that One Championship necessarily has. Critics are quick to point to the company’s financials: the company has accumulated over US$383 million in total losses since its founding, with US$110 million coming in FY2021 alone. Sityodtong might be one of the most charismatic founders in the region, but even he will find it hard to raise cash in this macro environment.

In this respect, it might make more sense for the company to leverage its existing IP through licensing instead of building them up from the ground. Gaming, collectibles, and potentially digital assets come to mind as key growth levers but are unlikely to yield a return on investment in the short term.

What sets One Championship apart is the tech DNA that VCs have injected into the company. In particular, its partnership with Facebook to produce VR content exclusive to the Oculus platform is something that’s pushing the edge of sporting entertainment and isn’t something you’d expect other fight promotions to try. And when you consider that it is the viewing experience, and not just the fight, that matters, this is product innovation at its finest.

But if that’s not enough, perhaps an entire continent’s support is. “I’ll just say it’s tribal,” Sityodtong remarked. “People want to root for people who look like them, eat like them, think like them, live life like them — and that’s resonating.”

Liked This Post?

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, subscribe to get posts sent directly to your inbox the moment it’s published.

And if you really love it, share this with someone else. It’ll make my day.

Thanks to Trevor and Yohanes for reading drafts of this.