Kopi Kenangan, the Shein of Coffee

The coffee chain that's brewing up a storm.

Howard Schultz’s trip to Italy in 1983 changed the way coffee was consumed.

Visiting the different coffee bars in Milan showed that the Europeans knew better than Americans how the beverage should be taken: a piping hot espresso served in a rustic cafe that made customers linger just to see a friendly face. Coffee was more than just a drink – it was an experience. The café was a third place beyond home and work where people could gather, relax, and talk.

Since Schultz brought the concept back to America and popularised it with Starbucks, sipping a coffee leisurely at a cafe has now become the way we drink it. Want a 1-on-1 conversation with someone at work? Do a coffee chat. A low commitment date? Grab coffee with someone. Somewhere with WiFi to get some work done? Hang out at the local cafe.

But things are starting to change. Coffee has become more of a necessity, although it still remains more than just a beverage that delivers a shot of caffeine into your body. Jokes about writers turning coffee into words and programmers turning coffee into code illustrate this best: it’s an acknowledgement that coffee is consumed daily, and just as importantly, publicly as well. There’s still a cultural element involved: where you get your coffee and how you drink it matters.

Kopi Kenangan has led this trend. In a region like Southeast Asia where median incomes are lower and consumers more price sensitive, they’ve managed to pioneer a grab-and-go model which makes drinking coffee as efficient as it gets. You still get a great cup of coffee, but without the idle chit-chat and the 7-dollar price tag that comes with it.

Investors have caught on as well. In December 2021, Kopi Kenangan raised a US$96 million Series C led by Tybourne Capital Management, bringing their valuation over the billion dollar mark. Including previous rounds, that’s US$333 million they’ve raised, from investors such as Sequoia Capital, B Capital, Alpha JWC, Horizon Ventures, and GIC to celebrities like Jay Z and Serena Williams. That’s a lot of interest and money in coffee.

When you see something like this, it makes you wonder what’s going on. This, coincidentally, is also a good sign that there’s something to be uncovered, which is why Kopi Kenangan is the subject of this breakdown. In this edition, we’ll cover:

Founding Story: Edward Tirtanata is no stranger to the F&B business. Before starting Kopi Kenangan, he ran Indonesia’s most successful artisanal tea lounge, but after realising coffee’s unique position in the F&B world, he switched his beverage of choice.

Product: Between Starbucks and sachet coffee, there was an opportunity in the medium market for premium coffee – a good product that was affordable, but not luxurious. Kopi Kenangan seized that opportunity and etched itself in that segment.

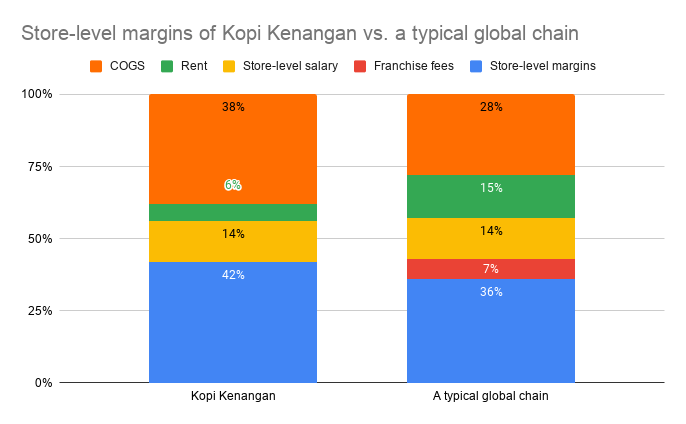

Business Model: Margins are low in the F&B industry, but Kenangan has managed to stay ahead of the competition by differentiating itself with a digital-first approach and keeping costs low with small storefronts.

Future: Tiranata is building a company that’s more than just kopi. With new food brands and Kenangan’s entry into FMCG, there are signs that we’re witnessing the beginning of a new F&B conglomerate.

Let’s jump right in.

Founding Story

Coffee might be Edward Tirtanata’s obsession now, but it wasn’t always the case.

After graduating from Northeastern University in 2010, Tirtanata spent a few years in Ernst & Young and other consultancies as a tax adviser. Inspired by his favourite teahouse in Boston, where he studied, he established Lewis & Caroll in 2015, an artisanal tea lounge that served premium tea which couldn’t be found in Indonesia.This made sense: Indonesia was the fourth largest tea leaf exporter in the world but did not have its own tea brand yet.

A few months after launching Lewis & Caroll, however, Tirtanata realised why this gap existed in the market: it was too difficult to attract customers. Premium tea was too upscale, and the way he branded his tea lounge - derived from English authors and tea lovers C.S. Lewis and Lewis Caroll - didn’t help as well. Sure, there were customers, but it was also clear that the concept was not resonating with the masses. Its product was better, but its price was not affordable to most.

Fortunately, Tirtanata didn’t have to look far. Although it was first and foremost a teahouse, Lewis & Caroll sold coffee as well, and it dawned on Tirtanata that this might be a better bet than tea. Most Indonesians were already drinking instant coffee, which was really just over-roasted coffee packed with flavouring and sugar. A decent cup of coffee at cafes went for Rp 40,000 (US$2.65), and if someone drank a cup everyday, that would add up to Rp 1.2 million (US$80), which was about 30% of the monthly minimum wage then.

Tirtana bet that people wanted an affordable and good cup of coffee, something between Starbucks and the sachets they drank from every day. This was also likely to be a better business than tea or any other F&B product. Consumers might not want to eat the same burger or pasta every day, but they’d happily drink the same cup of coffee. Plus, coffee has some addictive properties, which means that they could expect frequent repeat business.

In August 2018, he opened his first coffee shop outlet in South Jakarta with high school friend James Prananto. There was a twist to their business model: their store would be a grab-and-go offering with no seats available. The two of them had seen bubble tea chains explode into the scene with such a setup, and they reasoned that there was no reason this wouldn’t work as well. Smaller storefronts meant lower rents, and they hoped that this would offset the higher cost of ingredients that they were using for their coffee.

Kopi Kenangan - translated as coffee of memories - sold 700 cups of coffee in its first day. The name of their brand attracted eyeballs, and with each drink priced at an average of US$1.20 a cup, queues started to form outside their outlet as customers were curious to learn about this upstart brand. As Tirtanata remarked in an interview:

“I’m not sure why, but ‘kitschy’ branding works really well in Indonesia. Even on our first day of sales, we were able to sell 700 cups with hardly any marketing. People see the name, they are amused, and then they try. Because of that ‘lowbrow’ branding, people aren’t afraid that it will end up to be an expensive drink.”

A further burst of public awareness was created when some people started posting photos of their drink and tagging their exes on Instagram. Kopi Kenangan went mini-viral on social media, and sales increased accordingly. Within three months, the company was in the black, and Tirtanata and Prananto opened a second outlet. By then, they were convinced that the grab-and-go concept worked, and they followed this up by launching 14 more outlets in the next nine months.

Investors took note. Usage of apps like Grab and GoJek for food delivery had also become popular, which not only created additional distribution channels, but also normalised ordering food through apps. This created additional distribution channels, and it showed in Kopi Kenangan’s growth. Alpha JWC invested US$8 million in the company’s seed round in October 2018, and less than a year later, Sequoia India led Kopi Kenangan’s US$20 million Series A round. By then, the coffee startup had over 80 outlets.

The Rise of Tech-Enabled Coffee

Let’s start with what Kopi Kenangan offers: a fresh brew of coffee made from high quality Arabica beans sold at affordable prices. This sounds mundane now, but it was a novelty when Kopi Kenangan first started.

Unlike Starbucks or similar Western coffee shops, Kopi Kenangan’s offering is unabashedly local. Instead of hot Americanos with a dash of milk, they serve mostly iced drinks for customers to cool off from the hot Indonesian weather, and their drinks are all on the sweeter side due to local tastebuds. Each type of coffee is also given a creative name that evokes connotations of romance. Their signature drink, Kopi Kenangan Mantan, for example, translates to “memories of an ex-lover” in Bahasa Indonesia. It’s the kind of thing that gets people talking.

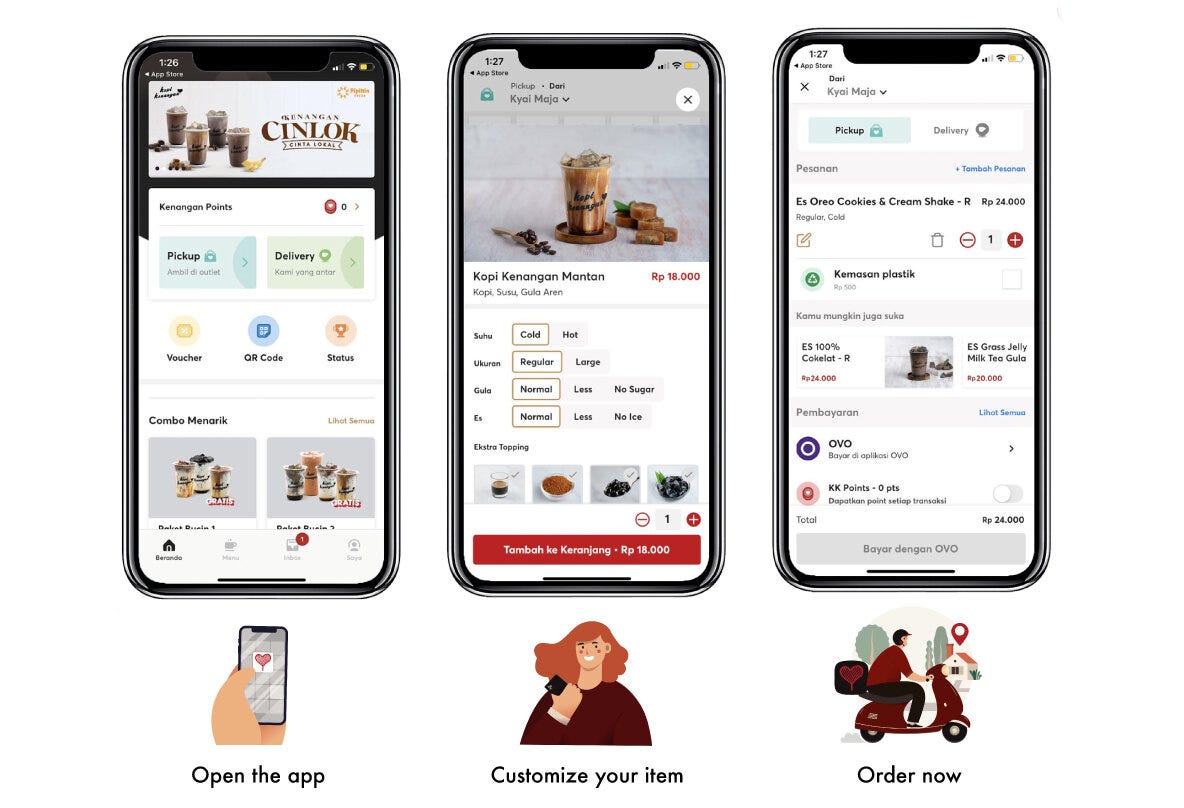

Novelty aside, Kopi Kenangan also promises a frictionless experience for customers. At the core of Kopi Kenangan’s “tech-enabled” offering is its mobile app, which allows for a completely paperless transaction. Customers can order their coffee in advance, saving the time they would normally spend queueing and waiting for the drink to be ready. Past transactions are analysed to recognise the customer’s coffee preferences, with the app aiming to become a personal barista that can make future recommendations. And of course, promotions and loyalty rewards are also broadcasted through the app to entice users to visit Kopi Kenangan again.

Order, pay, and collect your coffee. That sounds simple enough. But what if there isn’t an outlet within walking or delivery distance?

That’s the problem that Tirtanata and Prananto faced when Covid-19 hit. As lockdowns were imposed, the entire F&B industry came screeching to a halt and Kopi Kenangan was no exception. Transactions fell by 40%, and the company had to temporarily close outlets and shorten operating hours. The only silver lining was that customers still wanted their cup of Kenangan coffee, and delivery-friendly outlets saw orders increase by 50%.

This marked a paradigm shift in how Kopi Kenangan operated. Since customers couldn’t come to them, Tirtanata and Prananto figured that they would go to the customers instead. From the time working from home became a default, the data showed that residential areas performed better than those in the CBD, with outlets near suburban shophouses and gas stations standing out in particular.

The duo followed the trail. Using the US$109 million they had just raised in their Series B round, Kopi Kenangan focused on expanding in the heartlands. Locations for new outlets were chosen not for the amount of foot traffic it got, but also in a way that maximised delivery coverage. This was crucial. Food delivery on apps like Grab and Gojek would not be possible if a shop outlet was located too far away from the user, and so such customers would effectively be lost.

Kopi Kenangan set out to fix this and gradually turned this into a science. From 2019 to 2022, residential stores as a percentage of total outlets grew from 17% to 52% even as it expanded to over 600 stores in 45 different cities in Indonesia. And as Kopi Kenangan figures out to maximise its delivery footprint, it plans to eventually roll out cloud kitchens as well that serve only online orders. All to make getting a cup of coffee easy.

Business Model

The story wouldn't be complete without examining what goes on behind the scenes. Kopi Kenangan’s products might sell, but there’s still the question of profit. How does the company make money in an industry where profit margins are so thin?

In Shein: The TikTok of Commerce, Packy McCormick says that the reason Shein has grown so quickly is because they’ve taken China’s strength in manufacturing and applied it to the global market. He goes on to explain:

“This situation [Shein] holds parallels to TikTok which was able to take very standard China playbook UGC platform practices (e.g. directly paying creators) and apply them to Western markets. Selling fast-fashion through an app allows Shein to lean into its advantages to compete on three vectors it’s uniquely suited to win:

Price: “affordability”

Selection: “choice”

Retention: “addictiveness”

Shein’s ability to deliver on those three pillars are based on its advantages on the back-end (affordability and choice), front-end (addictiveness), and in the connection between the two. To win, it treats atoms like bits, and builds a system that connects supply and demand, in real-time.”

This might sound crazy, but I think Shein is a good comparison for Kopi Kenangan.

Like Shein, Kopi Kenangan is a direct-to-consumer and digital first company. They both sell consumer products that don’t seem differentiated in any particular way; you can easily find substitutes for the clothing and coffee that Shein and Kopi Kenangan sell respectively. And finally, both have somehow found a way to outflank the incumbents in their respective spaces despite their product not being far superior to their competition.

To be clear, Kopi Kenangan is playing a far easier game than Shein. It doesn’t have to do as much to score well across the same three vectors.

Addictiveness comes easily since caffeine is a substance that creates dependence, and Kopi Kenangan’s marketing efforts have made it the most popular coffee brand in Indonesia. Choice is another simple one since Kopi Kenangan has a much smaller base to cover; there are only so many ways you can have coffee. That just leaves affordability, which I think is the most interesting piece.

Low prices are possible only when costs are low, and Shein’s costs are low only in relation to what it would cost to manufacture something in another part of the world. That’s why they sell only to an international audience. Kopi Kenangan, on the other hand, enjoys no such advantage. They sell domestically, which means that low labour costs don’t benefit them in relation to the competition. That’s why they’ve had to keep costs low by setting up their own coffee roastery, and among other things, optimise on rent.

How do they do that? Well, Kopi Kenangan outlets take up 10 to 20% of the space that their competitors generally do. By having a grab-and-go concept and not having any seating space, Kopi Kenangan saves on rent since they take up less square footage. Plus, they are able to set up shop more easily in a variety of locations since it doesn’t take much to accommodate a kiosk. This is a big help given that rent is typically the largest line expense for most brick and mortar stores.

It gets better. Since customers don’t dine in at Kopi Kenangan outlets, there isn’t a need for it to compete for leases in locations with the highest footfall. In trying to attract customers, restaurants and shops naturally end up clustered due to Hotelling’s Model of Spatial Competition, which drives up rents. Kopi Kenangan, on the other hand, has no such need for physical storefronts to get customer attention. Because all it aims to do is maximise its collection and delivery footprint, they can open outlets in more obscure locations so long as customers can still physically reach them. That significantly improves profitability.

Shein defined what people now expect from online fashion retailers, and Kopi Kenangan is now defining what no-frills coffee should be like. But if that’s all there is to Kopi Kenangan’s business model, why doesn’t everyone just copy this?

If you're starting a new coffee chain, it wouldn’t be the hardest thing to do. Rocket Internet-backed Flash Coffee, for example, has taken this model and executed it in many countries including Singapore, South Korea, and Japan. But if you’re Starbucks, you can’t just remove seating in your stores because that’s why people customers visit you. And even if you decided a complete overhaul was necessary, it’s just not possible to get all your franchisees to change how they operate overnight.

In 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy, Hamilton Helmer lists counter-positioning as one of the conditions that creates the potential for persistent significant differential returns even with sigtnificant competition. As he explains, counter-positioning occurs when “a newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.” This is exactly what Kopi Kenangan has done with Starbucks and every other coffee chain which acts as a third place between home and the office. There’s not much the incumbents can do.

Of course, counter-positioning alone isn’t enough. It works well against incumbents, but doesn’t help with new up-and-comers who replicate the same model. What keeps Kopi Kenangan ahead of the competition is its flywheel which it has developed over the years, which only helps them become more efficient over time.

Branding - coincidentally another one of Helmer’s 7 Powers - has undeniably been instrumental in helping Kopi Kenangan fend off the competition at home, but it’s not clear if this will be the case when they expand overseas. If they want to avoid costly price wars, they’ll need a wedge (more on that later) to distribute their product since they’ll no longer have this flywheel. For now however, Kopi Kenangan’s model has been enough to keep it ahead of the pack and afloat - they reported being profitable in 2022 even after taking on heavy losses in the pandemic years.

The Making of A Conglomerate

“It’s so wild that we have tech-enabled coffee now.”

An ex-VC friend of mine said this to me recently, and I think it captures how most people feel about this space. Tech does create efficiencies, but it’s not clear how much value there is to be unlocked from selling coffee. There are only so many coffee variants you can sell, and there’s no chance you’ll ever have software margins.

Tirtanata and Prananto appear to have thought about that as well. After raising their Series C round, Kopi Kenangan has branched off into food items. This might sound normal; after all, lots of cafes have food on their menu as well, since this increases the average order value of a customer. But what most coffee shops don’t do is start new food brands that operate outside of their business.

It started with a piece of bread that customers could buy with their coffee. After hearing from customers that they enjoyed it, Tirtanata and Prananto decided it might be a good idea to attach a brand to it, calling it Cerita Roti. As brand awareness grew, the duo spun it out of Kopi Kenangan into a bakery chain. This process was repeated for other food items, creating brands such as Chigo (fried chicken), Kenangan Manis (soft-baked cookies), and Kenangan Heritage (a premium coffee mixologist and purist bar). They even launched their own bottled ready-to-drink early last year, becoming the first coffee chain to enter the world of FMCG.

This is not an obvious move. As Mario Gabriele highlights in his Starbucks analysis, coffee companies are growing by either improving efficiencies with the use of robots and automation, or building payments and reward programs in the hopes of building a super app. Integrating tech is the focus, not increasing the number of verticals that they are in.

All of this leads to one conclusion: Kopi Kenangan is an F&B conglomerate disguised as a coffee company. A company which has found a winning format typically expands quickly to capture market share, but Kopi Kenangan has not done this. Despite having a large warchest, its only overseas presence is in Malaysia, where they opened their first outlet in October last year. In comparison, Flash Coffee has locations in Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, Taiwan, and Indonesia, despite being founded only in 2020 and having less money in its coffers.

This is confounding, but makes sense if you consider that Kopi Kenangan is playing a different game. Instead of selling one product to a wide audience, they are focused on selling a wide variety of products to one audience: Indonesians. There’s no dogma as to what product they sell, or how they distribute it, so long as it remains profitable. If coffee and food products don’t have high margins, they’ll make up for it in volume.

So far, it’s looking promising. In FMCG, there are three things that really matter: selecting the right product, marketing it, and then distributing it. Kopi Kenangan has proven itself up to the first two tasks, but it’s not clear if it can handle the latter. Tirtanata and Prananto seem to have recognised this however; their selection of investors and strategic partners suggests that they are likely to get some help on this front.

Will they succeed? It’s too early to tell. But if history is any guide, it’s hard to bet against them. They stole a match on Starbucks, and they just might do the same to the Nestlés of the world.

Thanks to Trevor, Yohanes, and Joyce for reading drafts of this.

Liked this breakdown?

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, drop your email below and get posts sent directly to your inbox when they are published.

And if you loved it, share this with someone else. It’ll make my day.

YESSS! Can't wait to read this

so honored to be mentioned as your ex-VC friend 🤩