Grab: One App To Rule Southeast Asia

This is the most important company to watch if you want to know how the future of super apps, SPACs, and SEA will unfold.

“Cabs suck.”

That’s the two-word deal memo that Jason Calacanis wrote as a Sequoia scout. Although written as a joke to protest how Roelof was making him do homework on his investments, this observation has been spot on. It’s a thesis that has resulted in the founding of Uber, and the transformation of the mobility industry.

It’s also a thesis that has led to the founding of Grab, which was originally conceptualised as the Uber of Southeast Asia (SEA). Almost a decade later however, Grab has morphed into a super app where mobility is but just one product that is frequently used by consumers.

In this respect, you can argue that the student has surpassed the master. The best way to explain how this has happened is that Grab has drawn its inspiration from the west, but applied the lessons learned in the east. Today we’re going to look at this evolution through five sections:

Founding Story: Career transitions are a top reason why people enrol in B-School. By this metric, Harvard Business School has been a fantastic spawning ground for many startups, including Grab.

The Ride Hailing Wars: Grab is described as a super app now, but it wasn’t always clear that they would be the market leader. Winning a land grab requires speed and surgical execution, and Grab showed that it had both.

Grab Financial Group: When people talk about Grab, they’re typically referring to its mobility and delivery services. Yet what really cements the company as the dominant force in the region is its financial services arm.

Grab’s Playbook: Southeast Asia is a remarkably heterogeneous geography, with its population of 650M spread across 10 countries. In winning SEA, Grab wrote the playbook on how startups should expand in this region.

What’s next for Grab?: How concerned should investors be about Grab’s disastrous SPAC listing? A look at a Chinese super app might offer a clue.

Let’s get down to it.

Founding Story

“We all believe that if we get this right, we can literally go into the history books.”

When your opportunity cost is this high, the only thing you’d do is shoot for the stars. This is what Anthony Tan did.

Born into the family behind Tan Chong Motor Holdings, Anthony’s life was set. Tan Chong Motors was one of Malaysia’s largest automobile distributors, and at a young age, he was already Head of Supply Chain and Marketing. The plan for the son of a Malaysian Chinese tycoon was simple: go to Harvard Business School, earn a MBA, and take on a more senior position within the company.

But life had a different path in store for him. At HBS, he met Hooi Ling, a fellow Malaysian who would change his life. Ling (as she is commonly known) had spent her early professional life as an consultant, and was at B-school courtesy of a sponsorship from McKinsey. Unlike Anthony who spent most of his time focusing on the big picture, Ling was the meticulous operator who made sure that every detail was correct.

At a 2011 HBS competition, the two of them pitched a mobile app that would connect passengers directly with taxi drivers closest to their location. While Kalanick & Co started Uber as a black cab service which focused on convenience, Anthony and Ling thought that they should focus on trust and safety. Cabs in Malaysia were then (in)famous for ripping tourists off, and there were even reports of robberies by cabbies. Ling was one of those people who felt the problem acutely: each time she took a cab home after working late, she would pretend to be on the phone as a precaution.

The judges were apprehensive. They thought that SEA had too small a TAM for their venture, but clearly felt that Anthony and Ling had carefully considered how an existing model could be adapted for a new market since they crowned them runner-ups and awarded 25K USD in prize money.

This sum would be used to launch MyTeksi (before it rebranded to Grab) in 2012 even as each of them had their own personal difficulties. Ling had to honour her bond with McKinsey, and could only join full-time in May 2015 after returning to the consulting firm and then spending a brief time with Salesforce. As for Anthony, there was a little more drama: his father was unsupportive of the venture and threatened to disinherit him. His mother however, made an angel investment to support him even though she confessed that she didn’t understand the business model. This faith would be rewarded.

A Brief History of the Ride Hailing Wars

A key reason Anthony and Ling were willing to abandon their original career paths was because they had a window of opportunity that was closing. Uber had proven that its business model was viable, and it was only a matter of time before they expanded internationally. Being the first mover was the sole advantage they had, and they needed whatever head start they could get.

But many others had the same realisation as well, and competitors sprung up quickly. One such example was EasyTaxi.

Founded by Tallis Gomes and Daniel Cohen in early 2011, EasyTaxi was a fast growing and well capitalised company. Based in Brazil, the company was backed by Rocket Internet and had raised a Series A in late 2012, and then a 15 million Series B in June 2013 to venture into Latam and SEA. But beyond the capital they had raised, EasyTaxi had clearly absorbed some of Rocket Internet’s DNA, and it showed in the aggressiveness with which they acquired drivers for their platform.

For example, EasyTaxi’s staff would directly approach cabs with MyTeksi decals and get them to switch over. And when taxi drivers were confused as to how to install an app on their phone, EasyTaxi’s staff would not only help them install their app, but delete the MyTeksi app as well. Management did little to deny these allegations as well, with one EasyTaxi MD unapologetically remarking that “drivers are free to use any app they want on their phones.”

The early team would retaliate with the same strategies, showing that they weren’t afraid to roll in the mud with their competitors. These skirmishes would help them build operational muscle that would allow them to later take on the likes of Uber. But perhaps more importantly, the competitiveness that they showed would also give them the resource that they sorely needed - capital.

2014 was the first year that Grab really made its mark. Anthony was clearly busy all year, raising a 15M Series B led by GGV Capital in May, and a 65M Series C led by Tiger Global in October.

Yet this was barely enough. Uber had just closed a mammoth 1.2B round in June, and while most of that warchest would be used for markets such as China, it was inevitable that some of that cash would flow to their SEA operations as well.

Enter Softbank. Like other VCs who had backed regional competitors to Uber, Masa was on the hunt for someone to back, and he found that person in Anthony.

The Grab-Softbank relationship would begin in a manner that looked like a scene straight out from The Godfather. Masa had summoned Anthony to Softbank’s Tokyo offices and made Anthony an offer he couldn’t refuse: “If you take my money, good for me, good for you. If you don’t take my money, not so good for you.” There was no beating around the bush.

It was also a move that Masa had pulled earlier with Cheng Wei of Didi. But unlike Cheng who wasn’t actively looking to take on more money, Anthony did, and saying yes wasn’t an unpleasant experience. Softbank would invest 250M in Grab at the end of 2014, marking Grab 3rd’s round closed that year. Grab would pour those resources into growing by any means necessary - developing new products, entering new markets, and (mainly) engaging in a price war with Uber.

Another turning point would come in 2018. Softbank invested 7 billion in Uber in a round that many dubbed Uber’s “mini IPO”. This meant that Masa was now in the same position that DST Global’s Yuri Milner was in just years ago with Didi and Kuaiche - deeply invested in two competing companies.

Events unfolded as everyone expected: Grab and Uber announced a 6 billion dollar deal that would see Grab acquiring all of Uber’s SEA operations in exchange for 27.5% of stock.

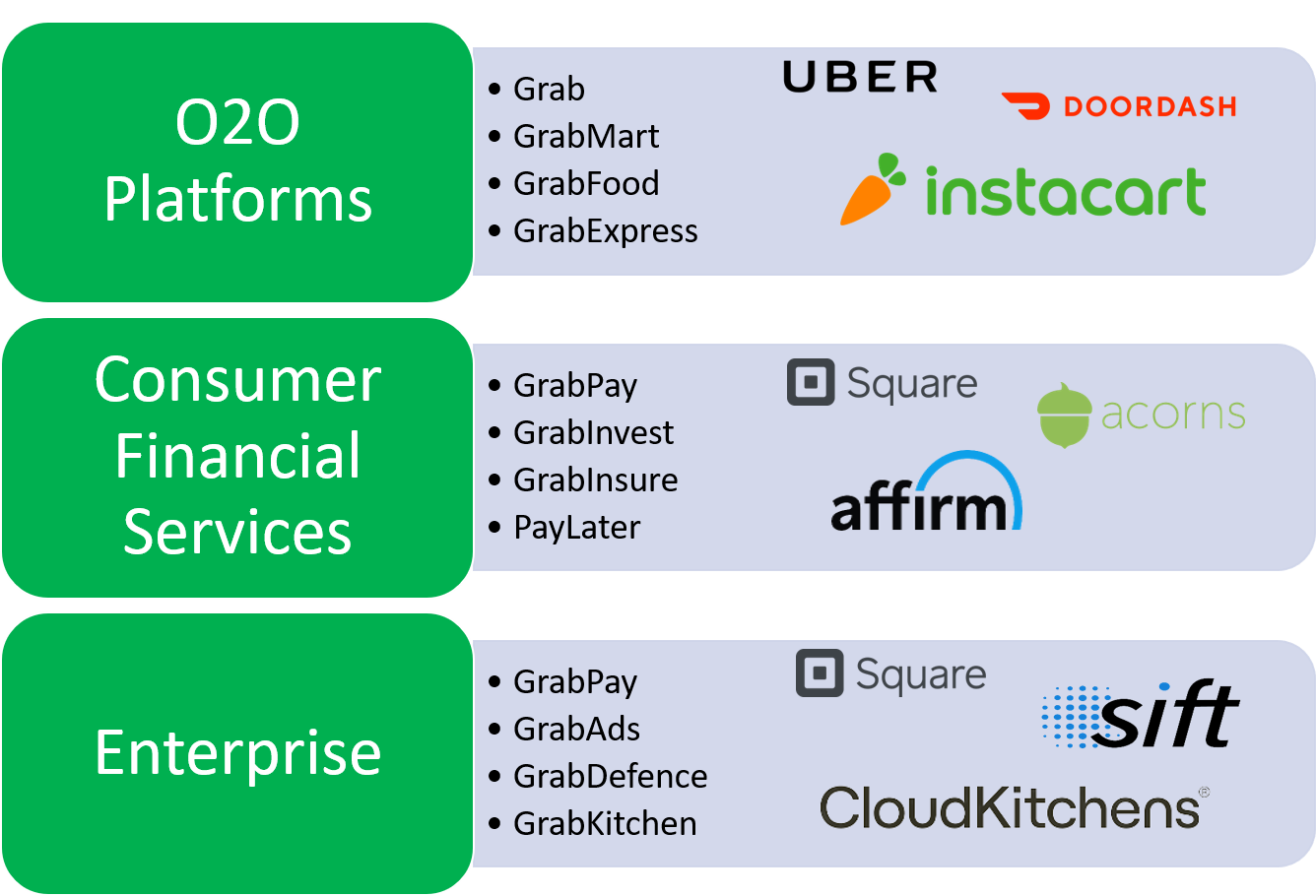

This not only made Grab the dominant player in most of the markets it operated in (excluding Indonesia, which we’ll get to later), but also paved the way for Grab’s expansion into food delivery with the acquisition of UberEats (which rebranded to GrabFood). It would also mark the start of Grab’s expansion into other O2O services such as groceries (GrabMart) and package deliveries (GrabExpress) as well as the launch of partnerships in less obvious verticals like travel booking and gift cards.

Grab Financial Group

If you hang around VC twitter long enough, you’ll see two cliches thrown around:

Every company is is a FinTech company;

All FinTech companies eventually become banks.

This has been true for Grab. Shortly after leading Grab’s Series B, Jixun Foo of GGV Capital started prodding Anthony to add payments to the app.

Foo had spent most of his time in China and had witnessed how mobile wallets increased the usage of WeChat and Alipay by removing the friction that typically came with beginning on a new platform. Instead, users could now try new services with a click of a button, leading to more time spent in-app and more products being used. The icing on the cake was that the platform would also have more data to work with when it came to product development.

To Foo’s mind, there was no reason Grab couldn’t do this since SEA shared the same conditions that enabled the mobile wallet boom in China:

90% mobile internet penetration;

rapid urbanisation; and

a traditionally cash-heavy society that was underbanked.

But there were also other concrete push factors. Because most transactions in SEA were cash based, Grab didn’t bother building a means to take credit cards up until 2016. This meant that cabbies (and regular drivers on GrabCar) had to deal with the hassle of handling change and making top-ups to pay Grab its platform commission. Fixing payments was thus the next biggest priority, and this showed in Grab’s rollout of its mobile wallet.

In 2016, GrabPay launched as a store of value. Depending on which country they were in, customers could top this up with ATM networks, online bank transfers, credit and debit cards, or at convenience stores.

It was antiquated, but GrabPay would improve rapidly over the next three years. Not only did it gain increased functionality through partnerships with Mastercard and Stripe, GrabPay also became a widely accepted payment method by third party merchants, whether it was a hawker stall selling chicken rice or a regional ecommerce giant like Zalora. If you came from the US, you’d think that a SEA version of Square had just sprung up overnight.

Grab would follow up on this momentum by spinning off its financial services arm to form Grab Financial Group. It would also offer new services in quick succession, going after virtually every consumer fintech category:

GrabInvest: a robo advisory investment service that allows users to invest small sums of money periodically or with every purchase

GrabInsure: microinsurance products with low premiums that provide coverage ranging from personal accident (which Grab already offered to drivers and passengers) to e-hailing and critical illness

PayLater: a BNPL service in partnership with Adyen

Credit: microloans disbursed to drivers and SMEs so that they can continue growing (while at the same time using Grab’s services)

The result? Grab has a budding financial services arm that might grow to become the Ant Financial Group of SEA. Financial services might be a low margin business, but by situating it in a high volume app, there’s a good chance that it shapes up to become the most profitable business unit in this decade.

To that end, Grab has arguably made significant headway by removing some of the obstacles that continue to plague other fintech players today, and in particular, regulatory risk. In 2020, it was one of two consortiums (the other being Sea Group) awarded a digital banking licence by the Singapore government after partnering with Singtel, a state-linked telecommunications company.

This is the kind of warm reception that other fintech players can only dream of, and its significance cannot be understated. While Chime has to deal with a prohibition against referring to itself as a bank and Ant Financial Group has to find another window of opportunity to IPO (if ever), Grab has been able to raise capital to expand its financial services arm and earn the trust of consumers by flexing its regulatory licences. In this respect, Grab has done as well a job as anybody in laying down a solid foundation for providing financial services.

The Grab Playbook

Grab has grown into the region’s most recognisable company. In doing so, it has developed a playbook that will come in handy for anyone who seeks to become a dominant force, regardless of whether it’s a B2C or B2B company.

Hyperlocalisation

For anyone who’s new to the region, there are two things to understand about SEA:

SEA is not just one market, but several heterogeneous markets;

Any VC backed business which is based in SEA must win regionally, and not just in any one single market.

SEA might have a population of over 650 million, but average GDP per capita (PPP) comes in at just over US$14,000. This means lower customer LTVs, which also means that any person who raises VC money must be able to conceivably become a regional winner since no country can single handedly support a venture scale business (with the possible exception of Indonesia which has a population of over 270 million).

That comes with it a huge set of problems. A product must not only work in English, but in nine other official languages. It also means having to deal with several different heterogeneous sets of cultures, business environments, and regulators. For comparison, Latam has close to 650 million people as well, but only has Spanish, Portuguese, and French as its predominantly spoken languages.

Grab didn’t lose sight of this. While Uber launched in SEA and started onboarding the traditional four-wheel taxi, Grab made sure to include the predominant type of transportation in each country. With services such as Grab TukTuk and GrabBike, Grab could not only onboard conventional taxi drivers and car owners with its GrabTaxi and GrabCar product lines, but also operators of other modes of transportation. What was considered “alternative” to a company with Western roots was conventional in this part of the world.

This thinking made its way to how Grab acquired riders and drivers as well, and it was clear from the early days that they were the consummate insider in the region.

When Uber expanded its Ice Cream Day campaign to SEA in 2015, Grab responded by offering the same promotion with durian, a local delicacy. This was a logistical challenge. Because durians have such an overpowering smell to the point that it is banned in airports and hotels, Grab had to come up with their own special packaging.

It worked. GrabDurian was such a hit that it sold out in Malaysia immediately, and it was clear that Grab was the people’s champion. “No foreigner would have thought to do that”, remarked Anthony.

Optimise for frequency

“At Grab, we have a saying that high frequency will always kill low frequency, and being very deliberate about the types of high frequency services that you provide is very core to how we think about designing the super app, and then the specific portfolio of services in each and every country.”

If there’s one sentence that can sum up Grab’s overarching product strategy, it’s the above by Grab’s President, Ming Maa.

Frequency of usage creates a habit, and a habit of using the app makes it easy for Grab to layer additional services on top of existing ones. Grab has added one product after another in the hopes of increasing time spent in-app, which correlates to the amount of revenue generated from each user. A look from their investor relations slide deck tells us as much:

This illustration of course isn’t perfect, but it provides a basis for building non-obvious product lines like video streaming (which didn’t do that well) and hotel booking (which did well enough it remains on the app). It also helps when consumers in each country have different needs from those in another. The core question that Grab needs to ask before deciding whether to add a new business line is quite simply “is this something that the customer will use often?”

Partnerships

Management teams have three choices when they want to build a new business line - they can buy, build, or acquire.

Grab has been spectacular at executing on partnerships. Although they have been able to attract some of the region’s best engineers and capital allocators (Ming was formerly at Goldman and Softbank), Grab has used partnerships to expand quickly while taking on less risk. These have been applied in several categories:

Grocery delivery: Grab partnered with Jakarta-based e-grocer HelloFresh to offer users fresh and frozen produce. This helped them compete better with Go-jek, a player with deeper roots and greater focus in Indonesia.

Live streaming: Hooq (now defunct) allowed Grab to offer video streaming, which increased time spent in-app even though it was not core to Grab’s business model.

Travel planning: Agoda and Booking.com allowed Grab to launch GrabHotels quickly, thus increasing the time spent in-app. This was particularly helpful since travel planning was already a saturated space, and building a product in this space would’ve yielded a negative ROI.

Payments: Stripe allowed Grab to offer GrabPay as a payments option for consumers outside the app for all sorts of ecommerce transactions

In cases where the partnership lies in a core business, Grab has gone further to acquire them after getting a sense of the synergies they can expect. This makes partnerships a useful tool for moving forward when the company doesn’t have enough conviction to make one-way door decisions: instead of committing early, Grab can take a wait-and-see approach without stalling product development entirely.

Work with regulators

“Hatred of bureaucracy alone isn’t enough to keep bureaucracy away.”

The above sounds like something Anthony might have said, but it was actually said by Flexport CEO Ryan Petersen in a recent podcast.

It’s also something that I think Western companies such as Uber have missed. In contrast to the aggressive language of disruption that Travis Kalanick has used, Grab’s management team has always emphasised that they are here to improve the lives of Southeast Asians. Their tone is collaborative, not competitive.

In a region where there is a deficit of trust, consumers look to regulators for guidance, and regulators have no qualms stepping in with measures that would be considered heavy-handed elsewhere. This means that B2C companies must tread carefully, and especially when your company not only offers financial services, but has a business model which might fundamentally redefine the future of work.

Grab has performed this balancing act extremely well, toggling between being conservative, opportunistic, and aggressive depending on the circumstances.

On one end of the spectrum, it has worked hard at establishing relations with different governments across SEA. On the other, Grab has shown that it is willing to defy regulators if necessary, having been fined by the Competition Commission of Singapore and Philippine Competition Commission during its merger with Uber.

Most of the time however, Grab has sidestepped regulatory concerns by buying companies which hold the requisite operating licences. Acquisitions such as Bento (which became GrabInvest), Kudo (which was folded into GrabPay), and Ovo (an e-wallet) allowed Grab to jumpstart its entry into new business verticals. In a region where regulatory approvals can take anywhere from a year up to three, strategic acquisitions can be the difference between being a market leader and being hopelessly behind.

Overcapitalise in a land grab

Without enough capital, none of the above strategies would have worked.

This is stating the obvious, but I think it’s worth mentioning. Founders who started ride-hailing startups in 2013 weren’t wrong about the size or obviousness of the opportunity, but just weren’t the right people to lead the company in a space that’s essentially a land grab.

In this respect, there might be no better person for the job than Anthony.

Many of Grab’s former employees have stated that Anthony’s superpower was fundraising, and in particular, his ability to sell a vision. VCs who invested early spoke of Anthony’s “fierce determination to succeed and prove his worth beyond the family he was born into” and how “the way he spoke to his mum” showed his personality and character. All this is highly subjective, but here Anthony seems to have cracked the code.

Of all the factors here, convincing Masa to give you money might ultimately be the most important thing you can do. There are brand name VCs, and then there are absolute whales. As EasyTaxi found out the hard way, having the former just isn’t enough sometimes.

Decoding Grab

Bear Case

The most important question remains: how much is Grab worth?

The market’s answer hasn’t been pretty. Grab went public via a SPAC combination with Altimeter in December last year, valuing it at US$40 billion. It was the largest SPAC listing ever, but shares fell from US$10 to US$7.15 by the end of the year, and then to the US$3 range after Grab reported its 2022Q1 earnings. That’s a 70% fall in valuation 3 months after going public.

Most of that has been a reaction to Grab posting US$3.6b in losses in 2021, the very same year it claims as its strongest yet. Even after removing one-off costs such as a US$1.6 billion convertible note and US$350 million in SPAC listing fees, Grab’s P&L column still doesn’t look good. For a company that raised US$4 billion in PIPE financing, there’s only so much more bleeding that can go on.

To make things worse, even with the unsustainable driver and passenger incentives that Grab continues to pay out, its user base has actually shrunk from 2020 to 2021. You can attribute this to Covid-19 which has created a whole new world of anomalies but this raises two fundamental concerns:

Product stickiness: is the app sticky enough that users will come back even after Grab scales back its driver and rider incentives?

Total number of users: Grab might be the regional consumer leader, but can it grow further without winning in Indonesia? GoTo has adopted an Indonesia-first strategy and it’s unlikely that they’ll be losing their lead anytime soon.

It’s anyone’s bet what happens, but I think we’ll get the answers soon. Ming has stated that he doesn’t see profitability and growth as mutually exclusive, but public markets have a way of forcing discipline when it comes to expenditure, and it’s hard to believe that Grab can continue bleeding cash at this pace.

At the same time, Indonesia is clearly a top priority for Grab, with Indonesia being the only country who has its managing director featured on Grab’s SPAC listing presentation. GoTo has been a thorn at Grab’s side ever since Anthony’s HBS classmate Nadiem Makarim founded Gojek, to the point that Masa has been rumoured to press the two to merge. If the bears are right, growth will slow significantly and it’s possible that Grab will never be profitable at all without serious cost cutting measures.

Bull Case

But I don’t think the situation is that dire. Lyft and Uber turned in their first profitable quarter in Q42021 after struggling for years, and it shows that mobility can be profitable. This will take some time, but will become clearer as mobility becomes a stable oligopoly where every player cuts back on riding and driving incentives.

What’s more interesting is Grab’s food delivery business. Restaurants still use GrabFood even though Grab’s take rate goes up to a whopping 30%. Unlike software companies who can afford to pay Apple and Google their 30% fee for using the App Store/Play Store, it’s difficult to see merchants do that in the F&B space since their margins are way smaller. The fact that GrabFood is Grab’s strongest business is perhaps the clearest sign that Grab has built up significant network effects and has a sticky enough product. It’s what happens when you become an aggregator.

Looking into the future, it’s also not hard to see that Grab will eventually build up moats in significant verticals. Ming has stated that beyond food delivery, Grab will be prioritising an expansion into ecommerce fulfilment and financial services. These are sectors that Grab is positioned well in, with Grab’s O2O infrastructure, as well as the array of licences and partnerships that it has entered into. In this case, it also helps that these are capital intensive, which creates another barrier to entry for others who are eyeing a slice of the pie.

I’m speculating at this point, but there are also a number of Grab products that are full of potential even if they haven't translated well to the balance sheet yet. Each of these are levers that could potentially become significant business units that transform how we think about the company.

PayLater: BNPL has proven to be a profitable business, and Grab will likely be able to roll out its BNPL offering easily through GrabPay (the very synergy that made Square acquire Afterpay for US$29 billion). This alone might unlock a large chunk of revenue for Grab.

GrabAds: Amazon used to shun ads in its early days, but ads have become a US$31 billion dollar business as Amazon grew, and it’s not a stretch to imagine that the same could happen for Grab. Network effects are a wonderful thing, and I think we might be underestimating how big this might get as Grab becomes a stickier app.

GrabDefence: When you have internal anti-fraud software that’s good enough to sell as a SaaS product, it’s a clear sign that you’re eating your own dog food and solving a real problem. This is more of an intuition about how Grab will likely be successful with product development, but it’s also possible that security becomes a huge P&L driver as SEA digitalises.

This isn’t to say that Grab’s valuation is justified.

Even if we used Grab’s numbers prepared in March 2021 (which looks rosy on hindsight), its SPAC listing valuation is on the higher side when compared to Meituan, a Chinese O2O super app which has probably inspired Grab’s strategy (recall how early investors wanted Grab to offer payments). A more reasonable valuation in line with Meituan’s numbers would value Grab closer to US$26 billion, 35% less than what it listed at.

But to say that Grab’s stock has grossly underperformed would be unfair. Tech stocks have taken a huge beating with the new macroeconomic environment. Netflix is down almost 70%, Snowflake down 55%, and even the money printer that is Meta is down 40%. Grab might be trading under $3 and down almost 70%, but that’s only in line with prevailing tech valuations. If you want to criticise Grab’s valuation, you’ll have to do the same for the wider Nasdaq index as a whole. And if you do that, you’ll also need to have predicted in December last year that we would see a Covid-19 resurgence in China, a looming food shortage, and a Russian invasion that might lead to WWIII.

Ultimately, Grab does have a path forward, and I think that purchasing Grab’s stock might be one of the easiest ways to buy a call option on SEA’s growing middle class. Grab alumni are already at the helm of many tech startups and companies, and in this regard, it’s possible that Grab is an example of the Peter Thiel line that the value created and value captured by a company are two independent variables.

Whichever the case, it’s undeniable that Anthony has delivered on the Grab vision to drive SEA forward.